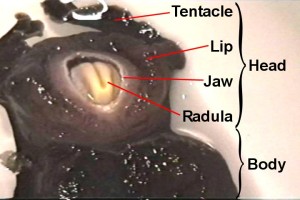

Supplementary MaterialOperant reward learning in Aplysia: Neuronal correlates and mechanismsBjörn Brembs, Fred D. Lorenzetti, Fredy D. Reyes, Douglas A. Baxter, John H. Byrne (HTML, PDF) Supplemental Video. Aplysia biting behavior. The consummatory phase of Aplysia feeding behavior (biting) occurs in an all-or-nothing fashion and is unambiguously quantifiable (1, 2). It consists of four phases: jaw opening, odontophore/radula protraction in the open state, odontophore/radula retraction in the closed state and jaw closure. Biting occurs spontaneously as well as reflexively, in nature as well as in the laboratory. If food is present, it leads to the ingestion of food through the buccal cavity. In this 8 s video sequence, the animal has positioned itself under the water surface (as they often do). Its tentacles (anterior) are at the top of the screen. The sequence contains the opening of the jaws, followed by the protraction of the radula (cream colored tongue-like organ) in the open state, the closure of the radula, the retraction of the radula in the closed state and the closing of the jaws.

To view this video, download a QuickTime

viewer. Quicktime video: 176x144

pixels (123,925 bytes) | 800x600

pixels (2,602,794 bytes)

Supplemental Methods 1.

Surgical procedures and in vivo recordings. Aplysia

californica (100-200 g) were obtained from Alacrity Marine

Biological Specimens (Redondo Beach, CA) and Marinus (Long Beach,

CA). They were kept individually in rectangular perforated plastic

cages floating in aerated artificial seawater (Instant Ocean;

Aquarium Systems, Mentor, OH) at a temperature of 12-15°C. Animals

were fed ~1 g of dried laver, 3 times a week. To help ensure that

all animals were in a similar motivational state, experimental

animals were food deprived 3-5 days before surgery.

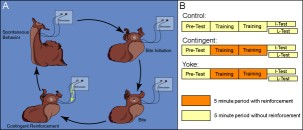

Supplemental Methods 2. Operant reward learning. The occurrence of spontaneous bites is dependent on a number of variables. While it can be observed in freshly caught specimens, it is comparatively rare. To successfully conduct experiments, certain measures need to be taken to increase the frequency at which this behavior occurs. To help ensure that all animals were in a similar motivational state, experimental animals were food deprived 3-5 days before surgery. One day after implanting the stimulating electrodes, the animals were fed a single bite of seaweed 30 minutes before the experiment to motivate the animal to search for food. Seaweed extract was prepared by incubating a 10 cm x 20 cm piece of seaweed in 300 ml of artificial seawater for 30 minutes. Pilot studies found seaweed extract to increase the overall probability of biting behavior to occur. Just prior to the experiment, 50 ml of the supernatant were added to 400 ml of fresh artificial seawater. The animal was then transferred into a round glass bowl (radius: 80 mm, depth: 70 mm) containing these 450 ml of diluted seaweed extract and the bowl placed on a mirror to be able to better observe the animal. The experiment was performed in a climate chamber at 15° C and 60% rel. humidity. Unrestrained in the bowl, the animal moved around freely and engaged in spontaneous behaviors (A). Throughout the experiment, the animal was observed and all bites recorded. A bite (see supplemental video) was defined as opening of the jaws and protraction of the radula. Before the start of the experiment, animals were assigned to one of three groups (B): i) a control group that did not receive any stimulation, ii) a contingent reinforcement group which received En2 stimulation whenever the jaws closed after a bite during training, or iii) a yoked control group that received the same sequence of stimulations as the contingent group, but the stimulation occurred uncorrelated with their behavior. Except for the different reinforcement schedules, all animals in all three groups were treated identically. Application of reinforcement was the only difference between training and test. In the early phase of the study, the animals were assigned randomly to each group. As the study progressed, the animals were assigned to each group so as to balance pre-test bite rate between groups. Experimental sessions consisted of four consecutive five-minute periods. In each period, the number of bites was recorded. The final test period was either immediately after training (I-Test) or 24 h after the beginning of the experiment (L-Test). A Grass S48D stimulator (Grass Instruments, Quincy, MA) generated 10 ms pulses for extracellular nerve stimulation (30 Hz, 3 s). Pilot studies determined that a suitable intensity of the stimulation was 8 V. At this voltage, usually no behavioral response could be observed. Occasionally, an animal (mostly yoked controls) would show a jaw opening without radula protraction or a rejection-like behavior (i.e., the radula appeared to be closed during protraction) to the first few stimulations only. Such responses were never observed spontaneously. If they met the definition of a bite (i.e., the radula was protracted), they were scored as bites irrespective of the subjective impression of the observer. Animals that were tested after 24 h spent the time between training and test in individual rectangular perforated plastic cages in aerated artificial seawater at 12-15° C. On the next day, the animals were placed back into the glass bowl with seaweed extract, but without being fed before the test. After the experiments, all animals were sacrificed and electrode placement verified. Only animals that produced 0 < n < 31 bites in the pre-test were used. Several experimenters independently replicated this experiment and all their data were pooled. Medium version | Full

size version

Supplemental Methods 3.

Biophysical correlates of the operant memory in B51. Animals

from a second behavioral study were anesthetized by injecting

a volume of isotonic MgCl2 equivalent to 50% of the

animal's weight. Buccal ganglia were removed and pinned on a Sylgard-coated

Petri dish containing artificial seawater (ASW). The composition

of the ASW was: 450 mM NaCl, 10 mM KCl, 30 mM MgCl2(6H2O),

20 mM MgSO4, 10 mM CaCl2(2H2O),

10 mM HEPES, with pH adjusted to 7.4. The ganglion ipsilateral

to the esophageal nerve stimulation was desheathed on the rostral

side. Desheathing was performed in the presence of high divalent

cation ASW solution, which contained concentrations of CaCl2

and MgCl2 that were three times the normal level. Osmolarity

was maintained by correspondingly decreasing the concentration

of NaCl. After desheathing, the medium was changed to normal ASW.

Supplemental Methods 4.

B51 cell culture and electrophysiology. Culturing procedures

followed those described in (5-8). Buccal ganglia from

adult Aplysia were incubated in 1% protease type IX (Sigma,

St. Louis, MO) at room temperature for 24 hours and then desheathed.

In pilot studies, B51 neurons in the buccal ganglia were first

identified by the electrophysiological methods described previously

and then dye-labelled with Fast Green (Sigma). B51 neurons were

removed from the ganglia by microelectrodes with fine tips and

plated on poly-L-lysine coated glass slides in petri dishes with

culture medium containing 50% hemolymph and 50% isotonic L15 (Sigma).

The cells were allowed to grow for 4-5 days and the medium was

changed on the third day. Culture medium was exchanged for ASW

prior to recording. It was found that neurite morphology coupled

with the size and the relative position of the cell in the ganglia

was sufficient to identify B51. Thus, these criteria were adopted

as the means of identification for all the neurons used in this

report.

Supplemental Discussion.

From postural adaptation to social interaction, operant conditioning

is one of the essential processes leading to the generation and

modulation of behavior. However, its analysis has been complicated

because most learning situations inseparably comprise operant

and classical components. Specifically, behaving organisms constantly

receive a stream of sensory input that is both dependent and independent

of their behavior. The classic debate as to whether one or two

processes account for the operant/classical dichotomy reflects

this entanglement (e.g., 9-14). Interrupting the operant

feedback loop by restraining an animal can at least partly isolate

classical conditioning from the operant components. Once isolated

from spontaneous behavior, in a number of systems the stimuli

have been traced into the nervous system to find the point of

convergence where the classical association is formed. Until now,

the convergence of reinforcement and the operant behavior has

remained elusive, however. References and Notes:

|